Dazu: Cliff-face carvings. Chongqing.

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. 2009

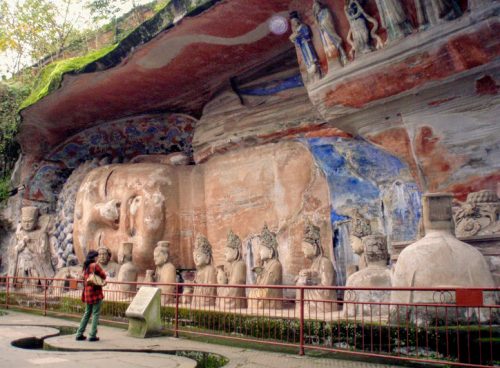

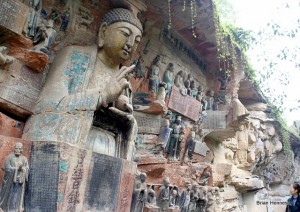

Dazu, a township near Chongqing’s western border with Sichuan province. The scene: a giant stone Buddha reclining, a smile of enlightenment on his enigmatic face as he enters nirvana. Next door, Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, is busy with her 1007 arms looking after the daily concerns of the faithful. Tending to the needs of supplicants who pray for a suitable marriage, a boy child, or for the resolution of some other temporal concern. Typical. There he is, taking a nap while she does all the work.

Dazu

____________________________________________________________

I separate from a small group of tourists listening to their guide explaining the layout and the history, and take note of the surroundings. This magnificent grotto art is chiselled into a U-shaped cliff-face surrounding a small ravine covered in soft green half-transparent vegetation. A tiny stream tinkles its way through the valley floor, fed by a spring somewhere above.

The carvings are world-heritage listed, and the most famous ones are the result of a 70 year effort by the Tantric Buddhist monk, Zhao Zhifeng in the twelfth century. Here. In the middle of nowhere.

Other carvings in places nearby were begun in the ninth century and were still being carried out in the nineteenth century during the last days of the Qing Dynasty. All of these heritage-listed sites on a par with the more famous grottos of Dunhuang in Gansu Province in northwest China.

It’s impossible to keep moving. You have to stop and take it all in.

But the late Autumn sky is turning grey and cold, and there is a possibility of rain. Should I stay or should I go?

I decide to stay, and climb down a few flights of uneven stone stairs into awesomely peaceful surrounds. That small stream is now draining through a dragon’s mouth, adding the soft sound of running water to the whispers of wind eddying around this natural sandstone amphitheatre.

The vegetation hides the contours and muffles any sound from tourists moving through. You can’t avoid contemplation in a place like this, I think to myself. It is almost mandatory.

No wonder. This is where Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism come together, absorbed into a typically Chinese amalgam of contradictory beliefs and customs. Unlike Europe, there have been no religious wars in the Middle Kingdom. Rather, an appreciation of what is best in all three systems, engineered to instruct the faithful on how to live a good and proper life. Creative practicality. Spiritual aesthetics and temporal instructions carved in perpetuity for the faithful. Up there on the walls.

Elderly faithful still live here. In their humble villages dotted along wooded mountain ridges which mark the south-eastern border of the fertile Sichuan basin. Farming the difficult slopes and stony valleys, and earning a few yuan from the growing number of tourists who come to see this oriental Trinity.

70 years. Zhao Zhifeng’s lifetime of carving and contemplation. Living on alms provided by the locals, and a spirituality nurtured in a small monastery on the ridge above. Continuing a job begun all those years ago in the Tang Dynasty. A lifetime. A blink of Buddha’s eye. Followed by another reincarnation perhaps. Maybe this fellow had been here before eh?

There were pilgrims and curious travellers here in those days also. Suzhou, the most beautiful city in the world at that time (near modern day Shanghai), provided the Buddhist upper class, and the surrounding countryside provided the Taoist worshipping peasants. Their Gods are represented here also. And underlying everything is Confucianism – a code for living rather than a religion – the bedrock for a spiritual symbiosis.

Would that us Christians could do the same. Here is the model. Here in Chongqing in the middle of China, the Middle Kingdom.

I circle the cliff-side panoply of art, theology, and instruction, and find myself before Buddha again. The other visitors have disappeared, and now it’s just me and Him. I sit on a cold concrete slab and look into his serene face.

A light puff of cool wet wind scatters a few brown leaves across the space between us before herding them towards an adjacent grotto. A moment of peace.

It has begun to rain. I rise, wrap my scarf around my neck to keep warm, and then look for the steps up to the exit above.

I am glad I came. Thank you Buddha.

I get a taxi to Dazu township, where the number of hairdressers per street astounds me. Prostitutes. Tourism on the rise. I find a decent hotel on the outskirts and after booking in, order three nice cold beers – the last two bottles costing more than the first. The barman taking me for a fool and squeezing me because I am a foreigner. It was only a few yuan, so I don’t bother complaining. He was such a nice man.

I know what this town will look like the next time I return.

.