Monastery

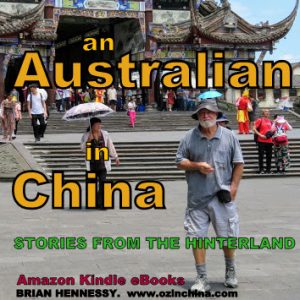

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China.

The first snow has fallen. A soft, white, layer of magic. A sparkling membrane of tiny, tiny crystals resting gently on the contours of the Maoya valley, its protective mountains, and the Khamba Tibetan town of Litang.

Monastery: in Litang

_________________________________________________________________________

Apart from the snow, nothing much has changed. It is just colder.

The main street in the old part of town is full of hardy nomads, their yak-skin coats, and their hill-climbing, articulated tulaji tractors; Chinese traders and their small stores and their pokey restaurants; jewellers, hammering away at their silver and brass creations; and the occasional mechanic with his tools and his oil and his machinery spilling out of his workshop and onto the footpath. The traders occupying small hole-in-the-wall premises. Workplaces by day, living and sleeping quarters by night.

Mesdames town-dwellers, looking elegant in their Tibetan gowns and western hats and shoes, going places and looking like they have important things to do. Grinning children on their way to school. Sweet little girls and naughty little boys.

Early morning is the time to get the feel of this place. Before the street-traders are up and at it. You can catch a nomad family herding a few newly purchased breeding stock (yaks) down the main street to somewhere out of town, or be disturbed by a pig checking the gutters for scraps. And today there is a strange, dare I admit it, mystical feeling of unreality as the early morning light stabs at the mist, trying to suffuse its way into town. A welcome but timid guest for the day.

The town is stirring. This little isolated community is getting ready for work. Like millions of isolated small communities worldwide.

What makes this place so special?

At 4000 metres above sea-level, Litang is the highest township on the planet, and the centre of a traditional nomad society. It’s changing though. The increasing number of middle-class Chinese in their SUVs who stopover on their way to Lhasa (3600 metres) are making sure of that. Chinese money is building hotels on the edge of town and changing the character of this ancient community. It’s not all bad news though: there is more employment, and the place is looking prosperous.

This is part of the old kingdom of Kham, the eastern one-third of the Qinghai Tibet Plateau, and the home of a proud Khamba Tibetan people whose culture is still pure. A living, breathing, praying, yak-herding, collection of valley based clans and isolated herdsmen and their families who insist on living their lives on their own terms. The townies however, live a more bipolar life as they struggle to hold on to what is old while adapting to what is new.

The greatest influence on this town however, is the monastery – with its lamas, monks, and Tibetan Mahayana Buddhism. On this part of the Plateu, the Yellow Hat sect.

There is no separation of church and state here, despite the secular administration in town. The thing that holds it all together is a theocracy. Although it has little formal power, it remains a moral and cultural force to be reckoned with. The people’s belief in their religion is so strong, you can almost touch it. It is a living, breathing entity. A reality of its own.

The monastery is a beautiful structure. Built in 1580 on the side of a hill overlooking the town, it is a visual blend of white, gold and deep-red. Ancient home to the 7th and the 10th Dalai lamas, it is a bastion of spiritual power. The political power that it used to project having been lost in the 1950s when China took charge of things.

Today this community of monks is thriving. The Maoya valley community sends its young men and women here, and there is no shortage of novices. For some, it’s a pathway to a spiritual life. For others, it’s just a better way of life than yak-herding. Orphans and poor nomad youngsters fill the latter category. Important point: the Yellow Hat sect does not return its members to the community after a short period of monasticism. Although these young people are here for life, they look happy enough to me.

Every morning, older townsfolk plus a few youngsters trek up the hill and around the walls of the monastery in an oxygen-starving circum-ambulation. An exhausting ritual that would test anyone’s commitment.

You have to see this expression of faith to believe it. Bent old ladies with walking sticks, good-humoured old men in white hats, a few mothers, and young folk hanging onto the free hand of a grandparent. The other hand fingering beads. Om mani beimei hom. Those with two free hands spinning their small hand-held prayer-wheels as well. Clockwise (the Red Hat sect do it the other way). Everyone stretching out in a long broken line of piety as they puff their way up the hill.

Inside the monastery, maroon-clad novices chanting their sacred texts. Their deep guttoral hum echoing around the walls and the halls of this Holy place.

I join the old folk on their circum-ambulation. These beautiful, humble, welcoming, old Tibetan people with their beads and their mantras, and their spinning prayer-wheels.

And I am moved. Beyond words. Beyond reason and rationality and culture. Some surreptitious tears first, then quiet sobs of deep emotion. I can’t help myself. I can’t stop myself. So I let it out.

I am happy. And so are the understanding faces of the beautiful, worn, brown, cracked, old, smiling faces that surround me. They have seen this reaction before and know its meaning.