Dunhuang: on the Silk Road

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. September/October, 2015

Located near the eastern end of the Silk Road, Dunhuang and its ancient Mogao caves contain an extraordinary number of religious artifacts, shrines, and secular manuscripts. Together they open a window into China’s fascinating history. Here is a little bit of it to whet your appetite (click photos to enlarge).

Dunhuang: on the Silk Road

____________________________________________________________

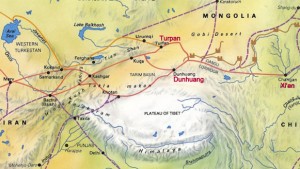

Dunhuang is approximately 2000 kilometres West from Beijing, and 1500 km northwest from Xi’an – the modern name for the old capital, Chang’an. It is located on the edge of the Gobi Desert, and is famous for its ancient caves containing a treasure trove of religious and secular material. It was a major stop on the Silk Road across China and Central Asia.

In its heyday, silk and other products such as porcelain, paper, tea, and bronze artifacts from China moved through Dunhuang on their way west to the Middle East and Europe. Goods heading east to China included camels, carpets, exotic fruits, glass, and horses.

Dunhuang was also a crossroads for two trading routes: the Silk Road between the Chinese capital Chang’an (now called Xi’an) and the West, and the main road from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and Southern Siberia. It was also a junction for both the north and south Silk Road routes which circumvented the great Taklamakan Desert in western China.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it was situated on the outer limits of the Middle Kingdom, and guarded the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor which led to Chang’an. Later, as a frontier garrison town, it anchored the Western end of the Great Wall of China. At that time it was the Tibetans who threatened Chang’an rather than Genghis Khan’s Mongols. The Mongols would arrive in the 13th century.

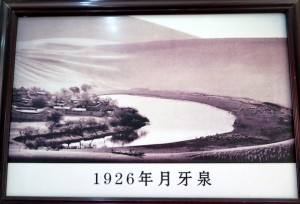

For the trading caravans travelling east along the Silk Road from Central Asia, Dunhuang was the last oasis before entering the protection of the Chinese state. From then on, the journey would be less dangerous. The perils of the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts were behind them, and the risk of attack by bandits was reduced.

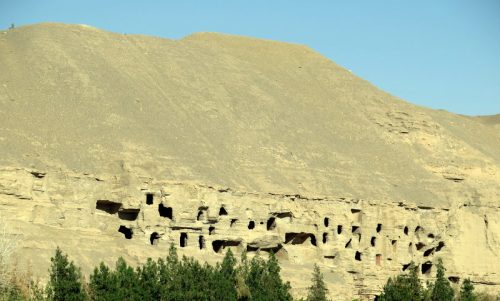

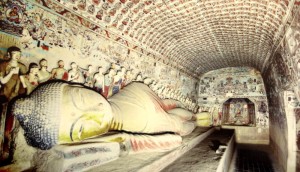

Having arrived safely in Dunhuang, Buddhist travellers expressed their gratitude by erecting shrines in caves dug into the soft earth of the surrounding hillsides. Over successive centuries, later arrivals added frescos, murals, and statues. Christian, Jewish, and Manichean artifacts can also be found there, indicating that many different peoples used this route. In fact, this is how Islam, Nestorian Christianity, and Iranian Zoroastrianism made their way to China.

Sadly, many of the best of these cultural treasures were looted by Western explorers and archaeologists. The most infamous among them being Aurel Stein who for a pittance persuaded a corrupt Chinese monk to give him access to priceless cultural and religious artifacts as well as a hidden cache of scrolls containing ancient texts and manuscripts.

Some of these documentss provide detailed records of commercial contracts, goods manifests, marriage agreements, and lists of bureaucratic requirements for travelling in Chinese territory – a great resource for modern historians who aim to tell us what life was like in this place all those years ago.

My train stopped there overnight. The huge Gobi Desert sandhills reminding me of the difficulties faced by the caravans, and the cool oasis water giving some idea how relieved and thankful exhausted travellers must have felt when they reached the safety of this border town on the outer limit of Chinese society.

These days, Dunhuang town contains 100,000 residents whose ancestry reflects its past: Chinese Han, and Muslim Hui people rub shoulders with Kazaks, Mongolians, Tibetans, and many other races. The descendants of traders, conquerors, and nearby local peoples.

The well-managed caves just outside town cope as well as can be expected with the modern hordes of Chinese package tourists who fly in to view them. Rushing from one cave to the next however, is not the way to do it. You need time to do this place justice and take it all in.

Next time I visit (probably by bus) I will linger longer. I’ll also do it in winter when there will be fewer people around. What’s a little snow.

Dunhuang. In Chinese eyes, the boundary line between civilisation and the barbarians – a quaint notion. Nevertheless, it’s a fascinating place. More so if you know your history.