Turpan: on the Silk Road

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. Sept/Oct, 2015

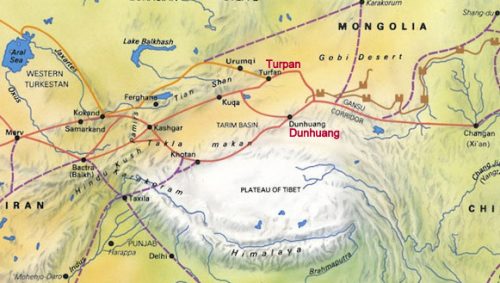

Turpan used to be a stopover on the northern Silk Road in what is now the province of Xinjiang in western China. It is adjacent to the eastern Tian Shan (Heavenly Mountain) on the edge of a Taklamakan desert depression called the Turpan Basin. It is 154 metres below sea-level (click photos to enlarge).

____________________________________________________________

I crossed a lot of desert to get here – in comfort and safety via a modern Chinese train. Those intrepid Silk Road traders however, did it the hard way – by camel. A slow, plodding journey across the desert, trusting to fate and good navigation. A dangerous enterprise.

The long train journey was worth it, though – my traveller’s curiosity rewarded by a dusty brown vista of the carefully preserved remains of an ancient township.

Rammed earth structures defying decay because there’s not enough rain to degrade them. Their original geometric symmetry sand-blasted by the desert winds which roar in from the Basin, into globular remnants of a Silk Road community and its organised society.

A people who lived in one of the harshest places on earth – a drastic environment described by the Lonely Planet today as China’s Death Valley.

A strong wind-storm can overturn trucks and trains here – that’s why it is home to the largest wind-farm in Asia. A moonscape of one-legged leviathans marching in step across the barren, forbidding terrain. Surreal. Jules Verne and his War-of-the-Worlds Martian invaders would have felt right at home here.

Yet, this place supplies the whole of China with succulent seedless grapes – the hot, dry conditions producing the sweetest harvest on the planet.

How can such crops grow in a desert? The ancient (everything here is ancient) Karez irrigation system explains why. Man-made underground channels tap the water-table draining the snow-melt from the Tian Shan and protect this precious resource from evaporation.

The underground water flows downhill and into the Basin where it disappears. In greater Xinjiang province in Western China, this Karez system is tapping subterrainian water everywhere – an engineering marvel comparable to the Great Wall and the Grand Canal. It’s just not as well-known.

This is Uyghur territory. The difficult relationship between local people and the Chinese government evidenced by the number of police – uniformed and plain-clothes – who attend a multiple wedding organised by local government officers. In the sky above, a sinister looking drone keeping an eye on things.

On the surface, a cultural feast of music, dance, and colourful clothing under a green arboreal canopy. Below, the reason for such abundance – the Karez. A metaphor perhaps, for what is seen and what is not seen in troubled Xinjiang province.

An oasis, irrigation, agriculture, ancient ruins, and a Moslem population with aspirations. Life in the harsh Turpan Basin: one of the driest, hottest, and most inhospitable places on earth.