Culture shock in China

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. DipT; BA; MEd; DipPsych. Psychologist

All change is stressful, and although we may not think so at the time, culture shock is a normal reaction to change. It is not a mental illness, and with a little self-knowledge it can be managed successfully.

If we hope to adapt to life in China, we need information on the external realities which may confront us. We also need information on the internal reactions which might be experienced as we make the transition from one culture to another.

These reactions may include uncomfortable physiological sensations, and uncharacteristic changes in emotions and behavior. There may be outbursts of anger; episodes of anxiety and depression, and brief periods of self-protective paranoia. Interpersonal relationships may be put under stress.

This article looks at the nature, stages, and causes of culture shock; and provides guidelines for managing culture shock experiences.

Culture Shock in China

______________________________________________________________

Content

- What is culture shock?

- Phases of culture shock

- Causes

- Coping strategies

WHAT IS CULTURE SHOCK?

Culture shock is a well-known but little understood term. Although most people have heard of it, few people understand what it means. Recent research has shed some light on this phenomenon, and as a result we have a better idea of what it is and how to manage it.

Definition. Culture shock is a reaction to the stress of living in an unfamiliar culture. It usually occurs when we are overwhelmed by too much information from our new environment, and when our responses to this overload are reactive rather than adaptive.

Note that some degree of culture shock is a normal reaction to living in a foreign country. Some people also adapt better than others. Adaptation is easier however, if we are aware of typical reactions to culture shock and are willing to learn new ways of coping.

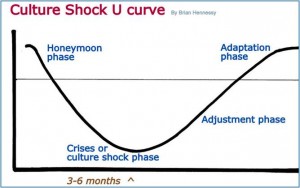

PHASES OF CULTURE SHOCK

The phases of adaptation to a new culture do not necessarily follow a fixed course. They can recur as new situations force continuing adjustment. They serve to outline a process toward adaptation rather than stipulate fixed milestones along the way.

Honeymoon. The first phase is typical of people who enter other cultures for vacations, business trips, and so on. It is characterized by interest, excitement, and ideal impressions of the new culture.

Why is this so? First impressions may be limited to places such as hotels, scenic spots, and exotic cultural icons. They may be reinforced by traditional Chinese courtesy and lavish Chinese hospitality. These seductive experiences insulate new arrivals from the reality of having to deal with the local culture on its own terms. Persons who intend staying longer may also enjoy a honeymoon phase.

Crisis. This second phase may emerge immediately, or it may escalate over time as negative experiences and reactions accumulate. It usually occurs within a few weeks after arrival.

Although individual reactions vary, generally speaking things start to go wrong. Minor issues become major problems, and cultural differences become irritating. There may be an excessive preoccupation with cleanliness. There may be increasing disappointments and frustrations. A feeling of being taken advantage of and a fear of being cheated is common. Becoming overly sensitive and suspicious are also typical reactions. Jostling crowds, rudeness, and smelly toilets offend our Western sensibilities. We find many reasons to dislike and criticize the new culture.

Adjustment. People in this third phase make their own adjustments. For example; some retreat into the safety of a foreign enclave.

Other folk embrace the challenges and move forward. These people learn from past experiences and maintain a positive attitude while acquiring new coping skills. They analyse situations, identify problem areas, and use a problem-solving technique to resolve difficulties.

They are patient with themselves, and know that adjustment can be a two steps forward and one step back process. Eventually the new culture begins to make sense. Negative reactions are reduced, and more positive experiences are enjoyed.

Adaptation. The fourth phase is reached when stable patterns of adaptation are demonstrated. Although full assimilation is improbable, it is likely that this process of adaptation will change the way we think and behave. We enjoy a new bi-cultural identity.

CAUSES

Dealing with cultural differences day in and day out can cause a certain amount of emotional wear and tear. The effort expended is cumulative. Here are a few things to be aware of:

Stress. Exposure to any new environment is psychologically stressful. Too much stress can also provoke a wide range of automatic physiological reactions such as the fight or flight response, and a weakening of the immune system. Living in a constant state of hyper-alertness wears us out, and we become vulnerable to illness.

Cognitive fatigue (difficulty thinking). The new culture demands a conscious attempt to understand things which are normally processed unconsciously back home. This change from automatic functioning to deliberate effort can be exhausting. Beware of burnout.

Role changes. Roles which are central to our personal identity may not exist in the new environment. For example; a high social status that we enjoyed in our local community may not be acknowledged in the new culture. Extended family roles which helped to make us feel valued and useful may be lost when we relocate to China. Self-esteem may suffer. Further, in China most people are assigned to a particular level (however subtle) in a Confucian hierarchy. There may be a mismatch between your hierarchical status and your professional role.

Personal shock. The many changes in our personal life take their toll. Personal shock can also be aggravated by aspects of the new culture which may violate our standards and values. For example: challenges to our values about personal privacy and public corruption may provoke this type of shock. We become acutely aware of cultural differences.

COPING STRATEGIES

It is possible to manage culture shock without making major changes to our behaviour or our lifestyle. The following strategies should prove helpful:

Preparation. Self assessment of our ability to adapt to a new culture is a good first step before we get on the plane. Not everyone can cope with the rigors of adapting to a foreign environment. Some people should never leave home.

Remember the five Ps: Proper Preparation Prevents Poor Performance. Culture shock can be minimised by doing a little research beforehand, and by organising resources which will aid coping and adjustment. For example; language lessons, books on China, expatriate websites, and so on.

An open-minded attitude about the new culture, and a willingness to change, are vital survival skills.

We should also be prepared for any prejudice or racial discrimination that might be encountered. All cultures are ethnocentric, and their members typically view their own cultural ways as superior. Rehearse creative or humorous ways of dealing with these insults beforehand. Be proud of your own culture. Grow a thick skin sooner rather than later.

Transition. If our basic needs are organised either before we depart for China or as soon as possible after we arrive, cultural adjustment will be easier. For example; accommodation, transport, schools, a proxy internet server (to get around the Great China Firewall), and so on. Then we can devote our energy to all the other important matters which will demand our attention.

It will also pay to learn something about stress and how to manage it. Nobody is immune from stress, and good stress management is vital for cross-cultural adaptation (google ‘stress’). Know your enemy. The one within as well as the one without!

Personal relations. Maintain a supportive network of family and friends. Invest in new relationships and learn how social relations are conducted in the new culture. For example, Westerners should know that Chinese people are less likely to form superficial friendships. Strong commitments and obligations can be attached to friendships in China.

Social interaction. Although knowing the local language is a quick way to understand a new culture, most of us arrive in China with little knowledge of Mandarin or ‘Putonghua’ (standard Chinese language).

A good first step is to focus on non-verbal behaviour patterns. Watching Chinese films or local TV is an entertaining way to do this. The best way however, is to get out of your insulated hotel, compound, or apartment block, and participate in the daily life around you. Break the ice and say ‘Nǐ hǎo’ (hello) to people. Don’t worry about your limited Chinese language or about committing some unpardonable social sin. In fact, Chinese people will appreciate your effort to communicate and will feel flattered by the attention you give them.

CONCLUSION

Sir Edmund Hilary prepared for his goal of climbing Mount Everest by learning everything he could about the mountain’s environment beforehand. He also understood his own strengths and weaknesses.

Facing the challenge of living in a foreign culture requires a similar attitude and approach. Sunzi’s “Know your enemy” and Plato’s “Know thyself” are timeless words of advice for those who would consider stepping outside their comfort zone.

– ooooo –

Buy our eBook, Get China Ready: Understand Chinese culture. Manage cultural differences, from Amazon Kindle eBooks (download their free App for your computer, laptop or tablet). Authors: Hennessy & Li. $9.99