The Tao of travel in rural China

Brian Hennessy. China Australia Consult. February, 2013

You need to have your wits about you when travelling independently across the countryside in China. Having said this, as long as you can speak a little functional Chinese language and have a normal ration of common sense and patience, your journey will be a rewarding one. If you take the usual precautions, safety should not be an issue (click photos to enlarge).

24 hours on the road in Yunnan

______________________________________________________________

I had done my hiking. I had walked along the Old Tea Horse Road and travelled to the Tibetan border. Now it was time to depart Bingzhongluo, a dramatically beautiful village environment at the top end of the Nujiang Valley canyon in northwest Yunnan Province. Thirty-two kilometres from Tibet, and adjacent to northern Burma, this special place is peopled by Drung, Lisu, Nu and Tibetan folk.

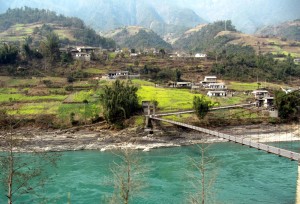

It’s a modest one-street town, with a few attached communities either spreading uphill to the snow-capped Gaoligong mountain range, or down towards the rushing Nujiang River below. To the north, the river leads to Tibet via a cleft in the range called the Stone Gate. To the south, it winds around the spectacular First Bend before tumbling through the canyon to Liuku 320 kilometres downstream. Liuku is the only gateway into this remote valley wilderness (See, https://ozinchina.com/2011/12/25/nujiang-canyon/)

My plan is to catch a small 15 seater bus to Liuku, and from there to make my way across country to Xiaguan and the ancient town of Dali, before flying back to my Chinese home in Chongqing on the Yangtze River.

You can never be certain of anything in China, so if you want a seat on any type of transport it is always wise to book the day before. So I find the ticket office beside an open market displaying pigs-heads and trays of roasted rodents among the fruit and veg, and book a seat up front next to the driver. The young lady behind the counter tells me that my bus will depart at 8:30am tomorrow, and that I should be there early. My ticket confirms the time: ‘离去: 0830.’

“Mingtian zaoshang, ba dian ban ma? (tomorrow morning at 8:30?)”, I ask just to make sure. “Ba dian ban” (8:30), she replies.

MORNING

Nevertheless, and because I have some experience in these matters, I make sure that I am at the departure point at 7:30am. Me, and a couple of hungry looking Tibetan dogs scrounging for scraps in the vacant market before first light.

Just as well. We depart at 8:00, and not at 8:30 (That young lady was trying to tell me something). Perhaps the driver just wants to get his working day done sooner rather than later. Saturday is market day in some of the villages downriver, and maybe he figures that this will slow us down.

After a slow trawl along the main street we hit the road. A few kilometres out of town we stop to pick up a fellow who has hailed the bus (as you do). The guy looks Chinese and I wonder what he is doing up here. He hands over a fistful of cash to the driver who slips it into a pocket inside his jacket and gets ready to roll again. Then the passenger does something unexpected. He asks for a receipt!

“Mei wenti” (no worries), says the driver (he got up early today, so he’s sharp). He leans over the engine bay, looks me in the eye, and asks quietly: “Qing gei ta nide fapiao.” (Please give him your ticket). So I hand it over, figuring that my seat is safe anyway. The Chinese police who inspect all buses are either looking for drugs from Burma or ‘criminals’ who might be heading for Tibet – they check ID, not tickets.

What a pity I am departing. This driver is in my debt now. If I was a local, I could have squeezed him for favours and locked him into a mutually beneficial relationship for life (Guanxi).

We continue our descent. Around the spectacular First bend of the Nujiang – one of the scenic wonders of China – and down to Gongshan where we fill up with legal passengers with pre-paid tickets. This small town squeezed between a river and a mountain is typical of all communities in the valley. You get the impression that if it didn’t grip tightly to the contours of the canyon wall it might collapse into the Nujiang and wash all the way down to Burma and the Indian Ocean. It’s a job to navigate the narrow thoroughfares and find the open road again.

Then stopping unexpectedly in the first largish village we come to. Market-day mayhem. Lisu minority people down from their homes on the steep canyon walls socialising and buying and selling provisions. Traffic jams of people and cars and motor cycles and the occasional animal blocking the road. Baskets of oranges, bottles of cooking oil, bags of rice, and racks and tables of cheap colourful clothing cluttering any roadside cavity and spilling onto the bitumen. This is why we left Bingzhongluo early.

Ethnic charm and roadside grunge. An enterprising family group cooking and selling baozi (dumplings), mantou (bread), and mian (noodles) over coals in cut 44 gallon drum stoves on a narrow footpath. Old ladies bent low from calcium deficiency huddling close by, stealing a little warmth from this improvised fast-food outlet. Some young mothers carrying children lashed to their backs, and others carrying baskets loaded with provisions which they will hump back up the mountain when it’s time to go.

The few who live across the river and in between villages and suspension bridges will risk it all when they return home via a fast ride on a single-cable flying fox. It’s a long way across, and it’s a long way down.

Meanwhile, the bus inches forward. Stealing space by mounting two wheels on the footpath, exploiting the gaps, and gaining territory via smart tactics and intimidating size. A bit like a rolling maul in a game of rugby really.

There’s no use being impatient. Places like these have their own rhythm, and in situations like this in China it’s better to be guided by Taoist philosophy and go with the flow rather than push against the current. So I sit back and enjoy the spectacle:

Car-horns beeping and barping uselessly – if the vehicles could move, they would. Unemployed young bucks swaggering through the crowd or playing pool in a dirty wooden hut between the road and the river. Pretty young girls smiling and giggling their way through this moving mass of minority people in a mix of colourful traditional clothing and cheap western jackets and jeans. Two or three old guys in peaked caps and odd military clothing saying “Ni hao” (hello) as they pass by. My grey beard once again helping to break the cultural ice.

Then suddenly, breaking out of the gridlock like a racehorse out of the gates and bolting down the bitumen to whatever is over the next rise or around the next bend.

Plenty of excitement and scenery. Each turn of the Nujiang opening another spectacular valley vista. Looking up to mountain ranges which reach heights of 4000 metres in places – both sides of the river – and marvelling at nature’s handiwork. The narrow bitumen road hurtling around blind corners, and the driver leaning on his horn to let oncoming traffic know we are coming through. Me taking photos of the view rushing past while fearing what might be around the other side of that next hair-pin bend. Exhilaration, fear, and blurred pictures of the prettiest part of the canyon.

AFTERNOON

Fugong is halfway down the valley, and that’s where we stop for fuel and lunch. When I scan what’s on offer on the footpath outside the bus-station (boiled fatty meat and rice, or noodles and leached greens) I lose my appetite. When travelling in China, a good rule of thumb is never to eat anywhere near a train station or bus stop. The proprietors of restaurants and street-stalls in these crowded places don’t care about the quality or safety of their food. They know that they will never see you again, and they don’t care. So thank God for my travelling rations: a pocketful of Uncle Toby’s chewy bars and some Cadbury’s chocolate.

Before we get going again, a young Tibetan lady asks the driver in Chinese where I am from. I overhear her and reply: “Wo shi Aodaliyaren he wo hui shuo ydianr dianr zhongwen” (I’m an Australian and I speak a little Chinese). She’s mortified that she has been understood, and her embarrassment is complete as the rest of the passengers see the funny side. Now I am friends with everyone. I answer the usual questions that foreigners are asked everywhere in China as we descend through the afternoon towards Liuku: e.g., “Ni gao shou” (how old are you?), “Ni zheng duo shao qian” (how much money do you earn?), and “Ni you duo shao haizi” (how many children do you have?). It’s all good fun.

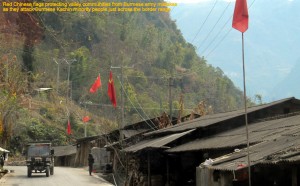

I notice that most of the villages we pass through have red Chinese flags flying on the top of tall bamboo poles and wonder why. The minority people who live in the Nujiang valley have no great affection for the Chinese government, so this apparent show of patriotism seems out of character. Then I learn that the Burmese army has been attacking their own rebel minority folk (the Kachin) who live across the border on the other side of the range. The border and the Kachin are so close, that some artillery shells have fallen on Chinese territory by mistake. So, rather than patriotism it’s, “Don’t shoot. This side of the range is Chinese, not Burmese!”

5:30pm finds me in a bare concrete Liuku bus station hoping to catch an overnight sleeper-bus to Xiaguan. Spring festival is coming, and all over China relatives are returning to their homes and villages so if you haven’t booked a seat beforehand there’s a good chance that you’ll miss out. But Buddha smiles on me and I snaffle the last bunk on the bus which departs at 8:30pm. At some point during the night we will cross the famous Mekong River, but hopefully I won’t be awake to notice. I’ve seen it before anyway.

It’s been a long day. A chewy-bar can only take you so far and my stomach is growling. So I decide to risk the fast-food being cooked under tatty umbrellas in the dusty windblown carpark outside. I avoid the meat and select noodles and two boiled eggs (safe), and something else with chillies that I can’t describe or name. I leave it in the bowl. I buy a bottle of pepsi for fluids (safe again), and settle down on a small plastic seat to wait until departure time. One ear open for squawking messages on the crackling public address system, listening for the word, ‘Xiaguan’. My destination.

There are no prosperous middle-class folk in bus stations in China – just ordinary folk (laobaixing) who struggle to survive. They stare a lot, but I forgive this apparent rudeness because it is genuine curiosity (foreigners are rare here). A group of happy-drunk men try to engage me in conversation, but when I tell them in Chinese that I can’t speak Chinese, “Wo bu hui shuo Zhongwen,” they leave me alone. An English teacher from a village upriver says hello and offers to tell me when boarding time is announced. Bless her kind Chinese heart – I don’t want to be left behind. She and her husband are returning to Kunming for Spring festival.

NIGHT

It’s time to join the scrum trying to board the bus. The driver tells me that I can’t stow my pack in the luggage compartment and that I must put it under the bunk. When I tell him that it’s too big to fit, he grumbles and allows me to squeeze it into a small corner in the rear of the compartment. Good. The other 39 passengers are bullied into placing their lighter gear underneath the bunks.

Later I find out why he wanted the luggage compartment empty. Two hours into our journey we deviate from the highway to small construction site and load bags of cement and building materials into it. This guy has his own scam going: he’s using the company bus to run a private delivery service!

We arrive in Xiaguan at 2:00am, and the usual thing is for the passengers to remain sleeping aboard until dawn. The bus station is locked anyway, so that’s what we do. Despite the racket caused by those happy drunks who, for the last five hours, have farted and snored their way across rural Yunnan.

By 5:00am I have had enough. Anyway, I need to get a taxi from this bus station to Dali Old Town which is about 15 kilometres away. If I wait any longer there will be a rush for the taxis, and I will be left cold, hungry, and tired – sans taxi. Stealing taxies in China is learned at an early age, and when push comes to shove the Chinese are better at this caper than I am.

But I’m street-smart now, and think of an adaptive strategy: exit the bus in the dark, get my pack, then grab the only taxi that I can see parked outside the bus station before anyone else wakes up. Literally and figuratively.

Problem: the luggage compartment (with building materials + my pack) is locked. Buggar!

And where is my driver? He’s got the key. So I go looking. I locate what seems to be a drivers’ crib-hut, and ask a feller inside to help me find my driver so that he can open the luggage compartment. He takes me back to my bus, and we find the driver fast asleep on a bunk inside.

I enjoy waking him up. That’s what you get for ripping the system off instead of providing a service for your passengers. But he won’t budge. Turns his back on me and tries to go back to sleep. Don’t I know that in China nobody is responsible for anything?

No I don’t. This foreign devil holds him responsible and shames him in front of the other passengers. Muttering ‘lowai’ this, and ‘lowai’ that (‘lowai’ means foreigner), he drags himself out into the cold and unlocks the compartment for me. I reward him with a false smile and an insincere ‘xiexie’ (thankyou) and gain big face for reminding this would-be capitalist that he still a servant of the people. I heave my pack onto my shoulders and wander off into a cold dark night in Xiaguan to claim that solitary taxi.

Not so fast. When I tell the driver that I want to go to Dali Old Town, he quotes me 80 yuan – the same amount of money I had paid for the overnight bus-ride from Liuku to Xiaguan. I’ve had enough of opportunists like him who exploit foreign tourists (and laugh about their gullibility behind their backs) so I eyeball him and call him a ‘pianzi’ (cheat). Twice.

Pride has got the better of me, and I refuse to bargain. Luckily, a private vehicle-owner who is cruising illegally for business pulls over and we agree on a price of 50 yuan. I jump in. But not before telling the taxi-driver how much less I would pay for the ride. Up him.

Twenty minutes later I am walking down the main alley in Dali with street cleaners for company as I search for a hotel that might be open at this hour. It is still black-dark and freezing cold. I find one which advertises a special deal for 100 yuan and wake up a sleeping door-man who in turn wakes up a night-duty receptionist who sleeps on a collapsible stretcher behind the counter.

She’s cranky, and wants to charge me the standard rate of 400 yuan. I invite her out to the front steps to show her the special deal advertised on the sign there, and insist that she honour the advertising. Surprisingly, the door-man supports me, and I tell him that he now has a friend for life. What a lovely old man.

God I am sick of the hustling, though.

Nevertheless, here I am in a nice warm room in Dali, awaiting the dawn of another day in China.

It’s been an interesting 24 hours.