Nujiang Canyon

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. November, 2011

The Nujiang (Nu River) Canyon is a spectacular 315 kilometre long marvel of nature in northwest Yunnan province in southwest China. The Chinese call it the Grand Canyon of the East: a direct comparison with the more famous Grand Canyon in the USA. Go there if you can.

Nujiang Canyon

____________________________________________________________

There is only one way into this beautiful part of China. It is difficult to get to, and is not on the way to anywhere else. A visitor must retrace his/her steps. This inconvenience however, is the reason why the Canyon remains untouched by the excesses of tourism.

The road in follows an old caravan route into Tibet. It’s a narrow two-lane bitumen secondary road which generally follows the riverbank as it winds its way north, every turn offering another aspect of this incredibly beautiful part of China. Sometimes it rises above a narrow gorge via a road cut into the cliff-face high above the rapids below. In other places it narrows suddenly into a single lane. This can be dangerous.*

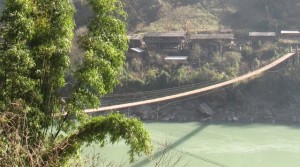

Steel-cabled suspension bridges traverse the gorge and connect small communities with the main road and the larger villages. Local people depend on these unstable constructions because river transport is impossible. Too many rapids.

The scenery is magnificent. Almost too good to be true. But there it is before your eyes: overwhelming memories of other beautiful places you have seen with its colour, scale and grandeur. Farms and villages mottling this riverine wonderland which is home to Nu, Lisu, Drung, and Tibetan minority people. Forests, streams and waterfalls adding their particular features to the bigger picture. Now I understand why one quarter of China’s flora and fauna species thrive here in this unique environment.

This wild river has its source in the Tanggula Mountains on the Tibet-Qinghai Plateau to the north. From there it flows southeast through a dry Tibetan gorge before tumbling south from the Plateau into a lush green Yunnan. The Gaoligong mountains (average height 4000m) then form its west bank and demarcate the border with Burma/Myanmar. The towering Biluo Mountains buttress the east bank and separate the Nujiang from its sister river, the Lancangjiang. Both ranges have snow-capped peaks which touch the stratosphere.

This is the World Heritage listed Three Rivers area where the Nujiang, Lancangjiang, and the Jinshajiang run parallel to each other for approximately 170 kilometres. Further downstream these watercourses diverge and become the Salween, Mekong, and Yangtze Rivers which empty into the sea in Burma, Vietnam, and Shanghai in China. At one point these three mighty rivers are only 70 kilometres apart.

Most people dwell in old wooden or new concrete block houses in small villages along the narrow riverbanks. However, some communities live in small clusters of thatch-roofed dwellings which cling perilously to the ridge-lines and slopes of the high canyon walls. People from these communities often use flying-foxes to cross the river in its more isolated reaches.

I travelled to the Nujiang from my Chinese home in Chongqing. A flight to Dali, the ancient independent Bai capital which was subdued by Kublai Khan in the 13th century, and then by road to Liuku the administrative centre on the southern end of the canyon.

Reading history along the way, I learned that the first Europeans to enter this part of China were French missionaries who arrived in the mid 19th century. These intrepid men built Christian communities and churches in the upper reaches of the Nujiang and Lancangjiang, close to the Tibetan border. Some of them were murdered and their churches burned by gangs of Tibetan youth directed by Lamas who resented what they regarded as a religio-political incursion into their area of influence.

The missionaries were followed by English and French explorers (a reversal of the usual pattern) who aimed to make a name for themselves by filling in the blank areas of existing maps. Some of them hoped to enter Tibet, but were forbidden to do so. So they contented themselves with identifying the higher mountains and discovering the sources and courses of the rivers they encountered. The botanists among them collected hundreds of new plant species. This was in the latter part of the 19th century.

As you can imagine, both groups of people endured extreme hardship as they followed their own stars. Today however, it is the missionaries and their efforts which have had the greatest influence on the local people. These men sought something other than personal fame, and the results of their altruistic labour can be seen today in the many active Christian communities and their churches which thrive in the canyon today (despite the efforts of the Cultural Revolution to erase culture and religion and recreate a ‘New Socialist Man’).

There are two largish townships north of Liuku: Fugong and Gongshan. You can find a three star Chinese hotel in all three locations. Cheaper varieties also if you are game. Finding a reasonable restaurant for an evening meal is difficult however. Isolated pristine locations such as Nujiang Canyon can lack tourist services. You need Chinese language to find and order a Chinese meal and negotiate the cost.

The head of the canyon is the best place to visit. North of Gongshan and just before you enter the village of Bingzhongluo, is the must-see ‘First Turn’ of the Nujiang where the flow of the green Nujiang waters is interrupted and redirected around ‘The First Toe’ of the Biluo Mountains opposite and below. Way below. The view from the road carved into the cliff-face of the Gaoligong Mountains on your side of the river will take your breath away. It will exceed your expectations.

And the first view of Bingzhongluo is spectacular also. Dramatic mountain ranges and jutting peaks surround this large village containing Tibetan, Lisu, Nu, and Drung communities. It spreads over a small fertile plateau which gradually descends to the river valley below.

A non-descript main street full of naughty Tibetan boys in the late afternoon, one hotel, and one backpacker-style guesthouse (The Lonely Planet’s description of accommodation is out of date: e.g., the Tea Horse Inn is out of business). And again, finding a place to eat is difficult if you don’t speak Chinese or a local language.

Despite the periodic burning of Christian churches by the Tibetans (this place is adjacent to the border) some Tibetans converted and now have their own church. You can also find a European style twin-towered Sacred Heart Catholic church in the nearby village of Zhongding. A single gravestone bearing brief testimony to the life and death of French priest Annet Genastier (1856-1937). I wonder if his life story is recorded somewhere.

Bingzhongluo; such a beautiful place with such a long history of inter-cultural and inter-religious violence, now living at peace with itself. Maybe the Chinese administrative presence helps to keep these old rivalries in check, eh?

The Nujiang Canyon: go and see it before it is dammed. This is on the cards, although plans have been suspended following a threat from the World Heritage organisation to de-list this site if the Chinese government goes ahead with this environmental outrage. At the moment, all that has happened is that the number of proposed dams has been lowered from 13 to 8. Preliminary drilling continues.

The Mekong is already dammed. So is the Yangtze. Will this national treasure experience the same fate?

–oo0oo–

* I passed an accident along the way: a blue truck had gone over the side and its occupants either killed by the fall to the rocks below or drowned in the Nujiang as the vehicle disappeared into a deep section of the river. Efforts to recover both the vehicle and the bodies failed. I was there at the time to see the truck rise to the surface before the cable broke as the vehicle jagged on an underwater boulder near the top. Back down into the depths again. That’s when everybody gave up and went home.

The New York Times. May 4, 2013

Plans to Harness Chinese River’s Power Threaten a Region

BINGZHONGLUO, China — From its crystalline beginnings as a rivulet seeping from a glacier on the Tibetan Himalayas to its broad, muddy amble through the jungles of Myanmar, the Nu River is one of Asia’s wildest waterways, its 1,700-mile course unimpeded as it rolls toward the Andaman Sea.

But the Nu’s days as one of the region’s last free-flowing rivers are dwindling. The Chinese government stunned environmentalists this year by reviving plans to build a series of hydropower dams on the upper reaches of the Nu, the heart of a Unesco World Heritage site in China’s southwest Yunnan Province that ranks among the world’s most ecologically diverse and fragile places.

Critics say the project will force the relocation of tens of thousands of ethnic minorities in the highlands of Yunnan and destroy the spawning grounds for a score of endangered fish species. Geologists warn that constructing the dams in a seismically active region could threaten those living downstream. Next month, Unesco is scheduled to discuss whether to include the area on its list of endangered places.

Among the biggest losers could be the millions of farmers and fishermen across the border in Myanmar and Thailand who depend on the Salween, as the river is called in Southeast Asia, for their sustenance. “We’re talking about a cascade of dams that will fundamentally alter the ecosystems and resources for downstream communities that depend on the river,” said Katy Yan, China program coordinator at International Rivers, an advocacy group.

Suspended in 2004 by Wen Jiabao, then the prime minister, and officially resuscitated shortly before his retirement in March, the project is increasing long-simmering regional tensions over Beijing’s plans to dam or divert a number of rivers that flow from China to other thirsty nations in its quest to bolster economic growth and reduce the country’s dependency on coal.

According to its latest energy plan, the government aims to begin construction on about three dozen hydroelectric projects across the country, which together will have more than twice the hydropower capacity of the United States.

So far China has been largely unresponsive to the concerns of its neighbors, among them India, Kazakhstan, Myanmar, Russia and Vietnam. Since 1997, China has declined to sign a United Nations water-sharing treaty that would govern the 13 major transnational rivers on its territory. “To fight for every drop of water or die” is how China’s former water resources minister, Wang Shucheng, once described the nation’s water policy.

Here in Bingzhongluo, a peaceful backpacker magnet, those who treasure the fast-moving, jade-green beauty of the Nu say the four proposed dams in Yunnan and the one already under construction in Tibet would irrevocably alter what guidebooks refer to as the Grand Canyon of the East. A soaring, 370-mile-long gorge carpeted with thick forests, the area is home to roughly half of China’s animal species, many of them endangered, including the snow leopard, the black snub-nosed monkey and the red panda.

Clinging improbably to the alpine peaks are mist-shrouded villages whose residents are among the area’s dozen or so indigenous tribes, most with their own languages. “The project will be good for the local government, but it will be a disaster for the local residents,” said Wan Li, 42, who in 2003 left behind his big-city life as an accountant in the provincial capital, Kunming, to open a youth hostel here. “They will lose their culture, their traditions and their livelihood, and we will be left with a placid, lifeless reservoir.”

As one of two major rivers in China still unimpeded by dams, the Nu has a fiercely devoted following among environmentalists who have grown despondent over the destruction of many of China’s waterways. The Ministry of Water Resources released a survey in March saying that 23,000 rivers had disappeared entirely and many of the nation’s most storied rivers had become degraded by pollution. The mouth of the Yellow River is little more than an effluent-fouled trickle, and the once-mighty Yangtze has been tamed by the Three Gorges Dam, a $25 billion project that displaced 1.4 million people.

For many advocates, the Nu has become something of a last stand. “Why can’t China have just one river that isn’t destroyed by humans?” asked Wang Yongchen, a well-known environmentalist in Beijing who has visited the area a dozen times in recent years.

Opponents say it is no coincidence that the project was revived shortly before the retirement of Mr. Wen, a populist whose decision to halt construction was hailed as a landmark victory for the nation’s fledgling environmental movement. Although he did not kill the project, Mr. Wen, a trained geologist, vowed it would not proceed without an exhaustive environmental impact assessment.

No such assessment has been released. Given the government’s goal of generating 15 percent of the nation’s electricity from non-fossil fuel by 2020, few expect environmental concerns to slow the project, even if the original plan of 13 dams on the Nu has for now been scaled back to 5. “Building a dam is about managing conflicts between man and nature, but without a scientific understanding of this project, it can only lead to calamity,” said Yang Yong, a geologist and an environmentalist.

Some experts say that China has little choice but to move forward with dams on the Nu, given the nation’s voracious power needs and an overreliance on coal that has contributed to record levels of smog in Beijing and other northern cities. Still, many environmentalists reject the government’s assertion that hydropower is “green energy,” noting that reservoirs created by dams swallow vast amounts of forest and field.

Also overlooked, they say, is the methane gas and carbon dioxide produced by decomposing vegetation, significant contributors to global warming.

“By depicting dams as green, China is seeking to justify its dam-building spree,” said Brahma Chellaney, a water resources expert at the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi. Mr. Chellaney said that Beijing had also failed to take into account the huge amounts of silt retained by dams that invariably deprive downstream farmers of the seasonal nutrients that have traditionally replenished overworked soil.

That the Nu has remained untouched even as China has corralled most of its rivers is a testament to the isolation of northwest Yunnan, a two-day drive from Kunming along a white-knuckle road carved into the canyon walls. Every few miles are the scars of recent landslides, a jarring reminder of the area’s geologic instability.

Despite the 2004 moratorium, work on the Nu River dams never really stopped, although Huadian, the state-owned hydropower giant, has ramped up planning efforts since the Chinese government removed any obstacles.

Late last month, as dusk fell on Maji, a proposed dam site, the sound of explosions echoed through the valley as workers, toiling around the clock, blasted test holes deep into canyon walls. Li Jiawang, 33, a laborer, said engineers were still trying to determine whether the rock was strong enough to support a dam several hundred feet high.

Huadian did not respond to interview requests, nor did the Ministry of Water Resources. But word that the project is moving forward has already drawn many outsiders, threatening to upend the delicate patchwork of ethnic populations. Hong Feng, 45, a migrant from Hunan Province who recently opened a roadside shop near Maji, said that most of his customers were dam workers from other parts of China. “We’re here to make our fortune, and then we’ll leave,” he said.

Most of the estimated 60,000 people who are likely to be displaced from the flooded, fertile lowlands do not have that option. They are largely subsistence farmers, and with nearly every level patch of land spoken for, many will be relocated to dense housing complexes like the one in New Xiaoshaba, a 124-unit project begun before the dam project was suspended.

“We used to grow so many watermelons we couldn’t eat them all, but now we have to buy everything,” said Li Tian, 25, a member of the Lisu ethnic group whose family was evicted from its land and who now works part time in a walnut processing plant.

While local leaders have been tight-lipped about relocation plans, they have worked hard in recent years to cast the project as a gift that will alleviate poverty in one of China’s poorest regions.

But Yu Shangping, 26, a farmer in Chala, a picturesque jumble of wooden houses hard by the Nu, objects to the notion that he and his neighbors are impoverished, saying the land and the river provide for nearly all their needs. “We’ve worked hard to build this place,” he said, “but when the government wants to construct a dam, there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Patrick Zuo contributed research.