Kangding

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. 2007, 2008, and 2011

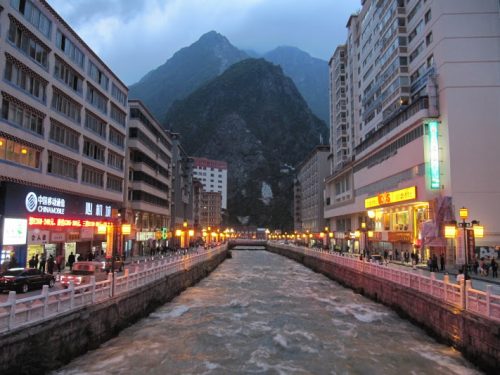

Kangding was once a trading town and cultural buffer on the old border between China and Tibet. When China annexed the eastern one-third of the Tibetan Plateau, this town became part of western Sichuan province. Today it remains a staging post for the long and tortuous journey to Lhasa. At an altitude of 2560 metres – halfway up the Plateau – it is a good place to stop for a day or two and acclimatise to the increasing height (click to enlarge photos).

Kangding. West Sichuan

______________________________________________________________

Kangding is an outpost town where Han Chinese influence gives way to a more noticeable Tibetan culture. In the past it was a successful multicultural community where wealthy merchants used to exchange tea from Ya’an on the edge of the Sichuan basin for yak hides and herbs and medicines from Tibet. Today it is a provincial town hell-bent on attracting Chinese tourists. It’s changing fast.

The road to Lhasa diverges from here: a northern route travels through the Tagong grasslands and over the 5000 metre pass on Chola Mountain before entering Tibet at Dege on the upper reach of the Yangtze (known locally as the Jinshajiang). The southern route climbs up to Litang and its nomad culture at 4200 metres on the Maoya Valley floor, before crossing the border and the Jinshajiang near the farming community of Batang.

One of the highest mountains in the world overlooks this isolated town and the surrounding area: Gongga Shan. At 7556 metres it dominates a wild countryside where trekkers go missing as a result of avalanches, mudslides, or foul-play. Backpackers have left warnings online about the behaviour of some of the young Tibetan men in this area. They’re no angels.

A steep river-valley stretches and squeezes the town into thin strips of cubist concrete on either side of a rushing Zheduo River. A mill-race of greenish cold water, tumbling down through the centre of town on its way to larger tributaries of the mighty Yangtze River below.

It’s a small pleasant place. Green and friendly in summer. Brown, snowy and withdrawn in winter.

I’ve made some friends here. A mother, her school-aged daughter, and a cousin or two who return from their colleges in Chengdu during school holidays. Mum runs a small restaurant on the main street near the bus terminal, and that’s where I eat when I pass through on my way to or from Litang up on the Plateau. A little pork with rice and a few fresh greens, plus some lukewarm Yijiuwuba (1958) beer to wash it down. I help the daughter with her English homework while mum looks after her customers. I have no idea where dad is. I don’t ask. He’s either bolted, or he is a migrant worker somewhere.

There’s a small binguan (hotel) next door. Nothing special, but its back windows look across the neighbourhood washing and up to a steep ridgeline jostling Kangding towards the river. In winter, it’s covered in snow. That’s where I camp. I met the laoban (manager) at the bus terminal the first time I visited. She was hustling for business, I was tired and disoriented, and that’s how I ended up in her humble digs. The sheets are always fresh there, so it isn’t as bad as it looks. Her husband is not sure whether he likes me or not, however. He grunted when I first said hello, so now I ignore him. Perhaps he thinks that I will spirit his missus away to the West one day when he is not looking. She’s his meal ticket: a good businesswoman who does all the work and keeps him in beer and cigarettes. I’ve never seen him lift a finger to help.

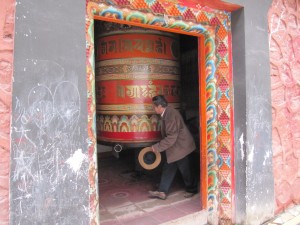

On the Western edge of town there’s a smallish Buddhist monastery built into the mountainside. From a distance, you can see curved golden rooflines highlighted against the green background vegetation. It is being renovated, and you can tell that something good is going on there. Unlike some temples elsewhere, this place is spiritually alive. There is a wonderful hum of activity as the monks and nuns go about their daily activities.

I like to wander around the courtyards and passageways of Buddhist temples and monasteries. This one has a few small niches surrounding the main building. Quiet places containing prayer wheels, racks of votive candles, and the occasional visitor enjoying a moment of contemplation.

I was sitting with my thoughts on a stone stool in a corner facing the prayer wheels – polished brass cylinders on top of wooden spinning handles at waist height – when a middle-aged nun approached me. Cropped hair, top to bottom maroon robes, and the sweetest, gentlest face you ever saw. I told her that I was an Australian who lived in Chongqing and that I liked these spiritual places. I regretted that my Chinese wasn’t good enough to explain that my spirituality was a mix of Christianity and Buddhism, and that I was on a Taoist wander around the countryside: the journey being more important than the destination.

Perhaps she guessed my thoughts. Saying ‘deng yi xia’ (wait a minute), she turned and headed towards a nearby flight of steps leading up to what I presumed was her solitary cell. Her elegantly ruffled robes betraying just a hint of sensuality as she ascended.

She returned with a gift of some CDs on Buddhism, smiled, and then disappeared back to wherever she had come from. Just like that. What a pity. I wanted to know why she had chosen this lifestyle. She had spoken good Putonghua (standard Chinese), so she wasn’t a local. There had to be an interesting story behind this renunciation of a previous life. Maybe I will see her again the next time I pass through here.

Across the road, and a little further away from town is a military barracks with a large concrete tarmac for vehicles. These places are dotted along highway 318 which runs from Kanding through Litang near the Tibetan border and on to Lhasa. The Chinese government is prepared for anything in this politically unstable part of the world and the barracks appear to be staging posts for large troop movements into Tibet should the young bucks there erupt into one of their periodic demonstrations against Chinese rule.

As well as spending a day or two here to acclimatise to the ascending altitude, Kangding is a good place to buy winter clothing. I get my thick denim shirts here, plus woollen socks, gloves, and a new beanie. I already have a woollen vest and jumper, my jacket has a few more years of service left in it, and my boots are still holding together. I’m ready.

My small bus departs at 6:30am the next day for the seven hour journey up to Litang. The climb up and out of Kangding getting the adrenaline flowing as the bus switches back and forth, labouring up the sides of a mountain ravine to higher ground above. If you look back, and if the weather is good, you can see the early morning sun reflecting off the snow on top of Gongga Shan.

The reports are true. This highway is one of the highest, roughest, most scenic, and most dangerous routes in the world. An exhilarating ride up through high mountain passes, and down into deep, deep valleys carved and weathered by ancient glaciers and extremes of climate – two hundred days with below zero temperatures in winter, and scorching hot days in summer. You wouldn’t believe it, but sunburn is a problem at this altitude. There’s not enough atmosphere to shield a big Western nose from the rays.

In the first part of the journey, there are occasional rides down through fertile valleys containing Tibetan farming communities. Then it gets serious again. Another long climb into the clouds. The road looping and switching in acute sharp angles as it claws its way along and up the steep sides of another ridge. At 4600 metres, a mountain pass provokes a brief headache and some shortness of breath. Oxygen deprivation. A mild inconvenience, more than compensated for by the view from the top. Awesome.

Then a rolling descent, an unstoppable swing around hairpin bends and blind corners of potential danger. The driver sounding his presence and his intent to demand right of way by blasting his horn, trusting us all to fate whether we are Buddhist or not. The Tibetans are praying. Me too. There are no atheists in buses on highway 318.

It is summer, and below the peaks and precipices, emerald green mountain grasslands roll across the Plateau into the distance. A cold clear sky sharpens perspective. Winter’s brown gone with the snow. Maroon, white, and yellow wildflowers carpet large swathes of the grasslands, while little bushes of purple flowers sprout in pleasant disarray around the protruding rocky outcrops.

Small herds of yaks graze on the slopes, and occasionally a nomad tent can be seen down on the flat. A whisp of smoke rising into the pure washed sky, reminding one that nomad families live and work in this beautiful but harsh environment.

Miles from anyone else. Miles from anywhere else.

The bus grinding and wheezing its way up to Litang. It’s another world up there.