Litang

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. 2006, 2007, 2008, & 2010

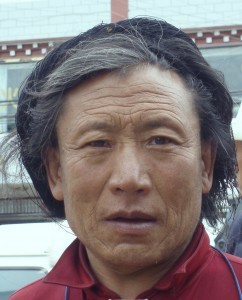

At 4200 metres, Litang is the heart of Khamba culture in the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau. The centre of the old kingdom of Kham. The inhabitants, although Tibetan, have their own character and history. They are a wild, proud lot. Noted for their independence and warrior spirit, they have fought both Western Tibetans and the Chinese in the past.

Litang

______________________________________________________________

The men revel in their masculinity. Past warrior glory is celebrated every time one of them mounts a horse. Small and short legged steeds, but quick off the mark, and easy to manouvre. To watch a galloping Khampa man leaning sideways to pick up a white silken scarf from the valley turf, or shoot an arrow or musket at a target, is to see courage and skill. To see a horde of them thundering past is to see history.

The ladies are elegant. Tall, straight, and handsome in their long sleeveless gowns pleated at the back. Well defined dark caucasian faces, acqueline noses, and oriental eyes. Married ladies wearing fetching hats, fashionable shoes, and a beautiful multicoloured apron. Unmarried ladies looking slim and attractive despite the layers of heavy clothing. Not a centimetre of flesh to be seen.

Nomad ladies dressed similarly, but without the blend of eastern and western style. Traditional felt hats, sensible shoes, and a weight of silver jewelry and precious stones. Looking beautiful, mysterious, and sunburned. As tall and elegant as their town sisters.

Mud and stone houses. Simple yet stylish in that unique Tibetan way. Litang, looking like the frontier town that it is, sitting with its back to high rolling hills, and facing the green valley grasslands to the front.

In the western distance, a forbidding stone massif, Mount Genie rises in defiance, as if to say, ‘come no further’. Its long bulk defining the western edge of the grasslands and guarding the approach to Tibet. Tradition has it that this mountain protects Litang. I think it protects Tibet. In the middle distance, the road to Lhasa turns north, searching for a way around this giant grey sentry.

A Tibetan monastery overlooks the town. A splendour of red, white, and yellow, this holy place is the beating heart of Litang. The secular authorities might look after temporal matters, but the real leadership of this community is vested in the Lama. You can’t separate the town from the monastery. It is one, a spiritual whole. A community bound together in belief.

No separation between church and state here. You can’t walk around the town of Litang without tripping over a monk. Clothed in red and gold, they are integrated in society. Their cheery sunburned faces ever ready to utter, a welcome ‘tashidelek’ to a visitor like me. Friendly fellows, they look like they have found the secret to life, the universe, and everything. Maybe they have. Must look into this one day…

My visit to Litang coincides with early summer, and the nomad people are stocking up, buying supplies and loading them onto their articulated diesel driven tractor-trailers. These vehicles would give a mountain goat a run for their money. Slow, chugging monstrosities, they are a cheap, reliable, and efficient means of transport if you are a nomad from the hills. A classic example of mechanical adaptation to a hostile environment. They are so ugly, they are beautiful. I want one.

Supplies? You can buy anything here. The main street is a collection of small independent enterprises. Clothing, shoes, hats, artifacts, it is all here. And you can watch a blacksmith forging tools, or admire a craftsman making jewelry. You can get your boots fixed on the street (I did), and eat in a myriad of small restaurants. Tibetan Yak and tsampa dishes; Chinese pork, vegetables and noodles; or cloned western food in Mr Zhou’s backpacker cafe (his yak steak and eggs are a specialty).

Litang is a contradiction, however. Its mood is changeable. Bi-polar if you like, just like the countryside. Underneath the atmosphere of genuine piety, and the observable blending of the secular and the spiritual dimensions, lies an uncomfortable truth. Khamba men can be hot-headed and violent. They can be dangerous.

These men carry long knives in their belts and they will use them in an argument. I know, I have seen the results. My friend Hero sports two knife wounds – one on his shoulder, the other on his stomach. Another man I was introduced to has had his face disfigured. A third, has a recent knife-slash on one hand. Predictable behaviour from a frustrated warrior culture.

This is the key to understanding their violence towards each other. They can’t beat their Chinese enemy. He is too powerful. So they live in the past and call it culture. Their courage is unquestioned. Crazy-brave, if you like. But it is sad to see these warriors reduced to frustrated, showy impotence.

The real men are the peaceful fellows up there in the hills herding their yaks. They don’t drink or smoke, and they take their religion seriously. They live their belief. They and their families, out there in the wild, living in their black tents on the green valley floors and the lush summer slopes of Eastern Tibet. The more fertile one third of greater Tibet. The real Tibetan people.