Managing Depression: via neuroscience

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. January, 2019.

Self-help information for expats in China who may have difficulty managing depression [sometimes associated with culture shock – see, https://ozinchina.com/2015/03/26/culture-shock-in-china/].

Derived from Alex Korb’s (2015) book titled, The Upward Spiral: using neuroscience to reverse the course of depression, one small change at a time. New Harbinger Publications Inc.

Managing Depression: a neuroscience perspective

_______________________________________________________________________

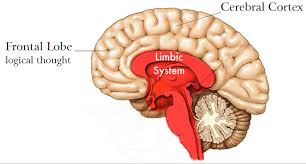

Assumption: Depression is a dysfunction in communication between the frontal lobe and the limbic system. It is possible to reverse a downward trend into depression.

NEURO ANATOMY ASSOCIATED WITH DEPRESSION

Mapping the brain. If we demystify the language, it may be easier to understand which part does what. And if we apply this understanding to the logic behind the neuroscience of depression, we may find it easier to arrest a downward spiral into an episode of depression. In fact, as Korb suggests, we may use this information to maintain better general mental health anyway. It’s worth wrestling with these unfamiliar scientific terms:

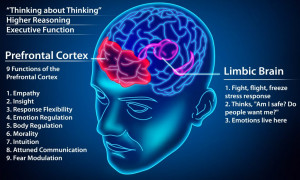

The prefrontal cortex – in the frontal lobe – sits behind the forehead and is the thinking part of the brain. It is the centre of planning and decision making circuits. It is also responsible for controlling impulses and motivation. Think of it as the CEO of the brain.

The limbic system is an ancient set of structures located much deeper in the brain and is the feeling part of the brain. It is responsible for things like excitement, fear, anxiety, memory, and desire. It has four regions:

- The hypothalamus regulates hormones and controls stress. It has a hair-trigger response which can make it difficult for us to feel relaxed and happy. In fact, too much stress can send the body into fight-or-flight mode. It can also cause depression.

- The amygdala is an ancient structure deep in the brain and is responsible for the perception of emotions. It detects fear and prepares for emergencies. It is the key to reducing anxiety, fear and other negative emotions.

- The hippocampus is also sensitive to stress. It is closely tied to the amygdala and hypothalamus, and is essential for learning and long-term memory. In a depressed person, it can be biased toward recalling sad events rather than happy ones.

- The anterior cingulate cortex focuses on attention. In a depressed person it can cause difficulty in concentration, and bias attention toward negative stimuli. This can affect mood.

In addition to the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system, two other regions play important roles in depression – the striatum and the insula. They also, are located deep inside the brain.

- The striatum includes (i) the dorsal striatum which controls good and bad habits. In a depressed person, reduced dopamine in the dorsal striatum is responsible for feelings of fatigue; and (ii) the nucleus accumbens which is responsible for impulsive behaviour. Reduced dopamine in the nucleus accumbens explains the typical lack of enjoyment reported by depressed people.

- The insula is responsible for emotional sensations and body awareness. In depression, it is more highly tuned to notice pain, elevated heart-rate, breathing difficulties, and other bodily sensations. This hyper awareness can turn molehills into mountains. Calming the insula can reduce pain and worries.

Point: we know a lot more these days about the anatomy of the brain.

NEUROTRANSMITTERS AND THEIR ROLES

Neurotransmitters are the brain’s communicators. They are chemical signals which transmit information from one brain-cell (neuron) to another across a small gap called a synapse (Fact: there are 100 billion neurons in the brain). For example:

- Serotonin improves willpower, motivation and mood. It aids resilience.

- Dopamine increases enjoyment and is necessary for changing bad habits.

- Norepinephrine enhances thinking , concentration, and dealing with stress.

- Oxytocin promotes feelings of trust, love, and connection. Reduces anxiety.

- Other neurotransmitters are also important: e.g., GABA (anti-anxiety), endorphins (elation and pain relief), and endocannabinoids (appetite and peacefulness).

- Other chemicals, such as BDNF help to grow new neurons (plasticity). Proteins in the immune system also have a role. Brain chemistry is complex and intertwining.

Different antidepressant medications may target different neurotransmitters.

Point: it is possible to improve communication across brain circuitry.

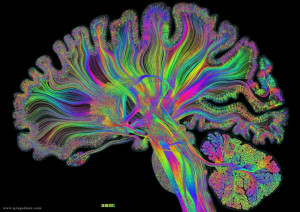

EVERYTHING IN THE BRAIN IS INTERCONNECTED

Within-brain commumication is analogous to the internet’s World Wide Web (www): i.e., everything is connected to everything else.

The good news is that if we focus positively on one practical behaviour it may have cascading positive effects on other behaviours via the brain’s interconnected circuitry: i.e., we can change the way the brain functions. For example:

- Thoughts and feelings of gratitude improve sleep.

- Sleep reduces pain.

- Reduced pain improves mood.

- Improved mood reduces anxiety.

- Reduced anxiety improves focus and planning.

- Focus and planning help decision-making.

- Decision making further reduces anxiety and improves enjoyment.

- Enjoyment gives us more to be grateful for, and keeps the upward spiral loop going. Enjoyment also makes it more likely that we will exercise and be social, which in turn, will make us happier.

The implication is that it is possible to modulate important circuits in the brain without taking antidepressant medication. For example, we can:

- Change dopamine and the dorsal striatum with exercise.

- Boost serotonin with massage.

- Make decisions and set goals to activate the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

- Reduce amygdala activity with a hug.

- Increase anterior cingulate activity with gratitude.

- Enhance prefrontal norepinephrine with sleep.

Point: these and other benefits create a feedback loop which causes more positive changes.

IN SHORT

Although the circuits in our brain are an interconnected web, it can be a fragile ecosystem. That’s a problem with depression: e.g., faulty thinking can affect many parts of the brain and send us spiralling downward.

However, by intervening early with just a few small life changes, we can reverse a downward trend. Then, as the brain begins to respond positively, the ecosystem becomes more resilient. This guards against future bouts of depression.

Because our neural circuits influence each other, the solution to our problems is not always straightforward. So, the next time we feel down, remember that our brain is stuck in a certain habit or pattern of activity. The best response then is to do something – anything – to change the negative pattern or context. For example:

- Can’t find a reason to get out of bed? Response: Stop looking for a reason; just get out of bed.

- Don’t feel like socialising? Go for a walk or a run.

- Can’t sleep? Think of something to be grateful for.

- Worrying too much? Stretch.

- Don’t feel like going to work? Go outside.

- And so on…

In neuroscience terms, once our hippocampus (in the ‘feeling’ part of the brain) recognises a changed context, it will trigger the dorsal striatum to start acting out better habits. Better still, it may trigger our prefrontal cortex (the ‘thinking’ part of the brain) to come up with a good reason for the change.

Although change may not be immediate, we can activate important circuits just by thinking about them. Given change and time, a downward spiral into depression may be halted and reversed.

Point: we can change the way we think, feel, and behave. We can change the way our brain behaves.

—ooo0ooo—

In the case of a major depressive episode: a caution

The above suggestions together with antidepressant medication and counselling offer the best hope for successful treatment.

Brian Hennessy, DipT; BA; MEd; DipPsych. Psychologist

_______________________________________________________________________