The Silk Road by train

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. September/October, 2015

Traversing the Silk Road by train in Central Asia. How does one condense so much ancient and modern history into one short article? A difficult task. So I will limit my observations to a traveller’s general impressions rather than specific descriptions of the places visited (click photos to enlarge).

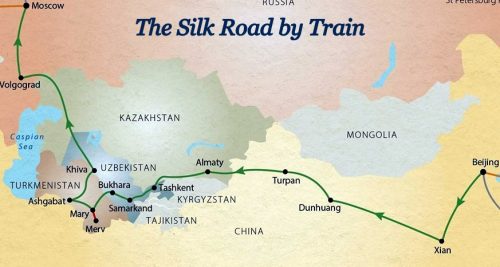

The Silk Road by train

______________________________________________________________

Background

There were many branches of the Silk Road. Their general direction however, was west across Central Asia and on to Europe via the Middle East. My journey visited the most important places along this route.

Point: there was no direct flow of trade between China and Europe, rather it was a succession of commercial transactions between adjacent oases, khanates, and kingdoms.

In peaceful times, trade flourished. At other times it was squashed by invasion and terror, most notably but not limited to, Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes which rampaged across the Central Asian region.

Nevertheless, in its heyday, silk and other products such as porcelain, paper, tea, and bronze artifacts from China found their way to Europe. It wasn’t all one-way traffic however. Goods heading east included camels, carpets, exotic fruits, glass, and horses. Religions also: for example; Buddhism, Islam, Nestorian Christianity, and Iranian Zoroastrianism.

China

_________________________________________________________________________

XI’AN

The eastern terminus of this fabled route was the ancient city of Chang’an. In 221 BC it was established by the first Chinese Emperor, Qin Shi Huang, as the capital of the new Chinese state.

Later, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Chang’an benefited from its exposure to commercial and cultural influences from central Asia. During this period it developed into the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the world.

Its contemporary name is Xi’an, the home of the famous Terracotta warriors. A fitting place to begin this modern Journey to the West.

During the early Tang Dynasty, a Buddhist monk called Xuanzang made the original Journey to the West (described in historical records, literature, and film). Although his motivation was spiritual – to obtain original Buddhist sutras – Xuanzang proved to be a good diplomat for China. Improved relations with central Asian leaders created trading opportunities.

Trading had its perils though. The caravans which journeyed east to China and west across Central Asia had more than bandits to contend with. The greatest enemy was the desert whose sands cover the bones of many traders who perished after losing their way between one oasis and the next.

Travelling across the desert today in the comfort and safety of a modern train, one marvels at how these hardy people did it.

DUNHUANG

For the caravans travelling east, the last oasis before Chang’an (Xi’an) was called Dunhuang. Those who arrived there safely knew that the rest of their journey would be much easier. The Buddhists among them expressed their thanks by erecting shrines in caves dug into the soft earth of the surrounding hillsides. These are the Mogao caves, the source of many looted cultural and religious treasures now located in European galleries.

Eventually, these caves became repositories for period documents and cultural artifacts. A treasure trove of secular as well as Buddhist cultural history, right down to account records of Silk Road transactions, formal complaints, and Chinese government bureaucratic requirements.

Our train stopped there overnight. The huge Gobi Desert sand hills and the oasis water reminding us of how relieved and thankful exhausted travellers must have felt when they finally reached the safety of this border town on the outer limit of Chinese society.

The dangers of the desert were behind them, and the protection of the Chinese state lay ahead of them as they prepared to continue their journey down through the Hexi Corridor to their final destination – the civilised capital of Chang’an.

These days, Dunhuang town contains 100,000 residents whose ancestry reflects its past: Chinese Han, and Muslim Hui people rub shoulders with Kazaks, Mongolians, Tibetans, and many other races. The well-managed caves just outside town cope well with the modern hordes of Chinese package tourists who fly in to view them.

Dunhuang, in Chinese eyes, the boundary line between civilisation and the barbarians. A fascinating place. More so if you know your history.

TURPAN

Turpan is adjacent to the eastern Tian Shan (Heavenly Mountain) on the northern edge of the Turpan Basin – a dry forbidding desert depression, 154 metres below sea-level in the Taklamakan desert. There are ancient ruins here. Silent, windblown monuments to a lost community. Rammed earth structures surviving because there’s not enough rain to degrade them. The desert winds that roar in from the Basin sand-blasting their original geometric symmetry into defiant globular reminders of what once was.

A strong wind-storm can overturn trucks and trains here – that’s why it is home to the largest wind-farm in Asia. A moonscape of one-legged leviathans marching in step across a barren, forbidding landscape. Surreal.

Yet, this place supplies the whole of China with succulent seedless grapes – the hot, dry conditions producing the sweetest harvest on the planet.

How can crops grow in a desert? The ancient (everything here is ancient) Karez irrigation system explains why. Man-made underground channels tap the water-table draining the snow-melt from the mountains and protect this precious resource from desert evaporation. The water flows downhill from the mountains and into the basin. In greater Xinjiang province in Western China, this Karez system flows for thousands of kilometres – an engineering marvel comparable to the Great Wall and the Grand Canal. It’s just not as well-known.

This is Moslem Uyghur territory. The difficult relationship between local people and the Chinese government evidenced by the number of police – uniformed and plain-clothes – who attend a multiple wedding organised by the local government. A cultural feast of music, dance, and colourful clothing under an arboreal canopy nurtured by the cool, clear waters hidden below.

A people, an oasis, irrigation, agriculture, ancient ruins, and life in the harsh Turpan Basin: one of the driest, hottest, and most inhospitable places on earth.

Yet trading caravans passed through here all those years ago.

Kazakhstan

_________________________________________________________________________

The border between China and Kazakhstan (now) and the old Soviet Union (then) is a no-man’s-land of barbed-wire, observation towers, and electronic surveillance. A black hole for mobile phone and internet communication. This is where East meets West, and it takes a while to navigate through the border formalities. Although the Kazakh troops are friendly, their system isn’t. Cultural divides are always difficult to cross.

ALMATY

Almaty in the southeast of Kazakhstan abuts the southwestern arm of the Tian Shan and the border with mountainous Kyrgyzstan. A valley society politically less-mature than its larger northern neighbour.

The Silk Road passed through Almaty on its way to other oases which were fed either by the Afghanistan and Iranian Plateaus, or by two famous rivers – the Syrdarya (Jaxartes) and Amudarya (Oxus) – which drain into the remains of the Aral Sea. Alexander the Great crossed the Oxus on his way to India.

Almaty is a quietly beautiful place. Its backdrop is the snow-capped grandeur of the Tian Shan (a hot-spot for winter sports), and the city has a progressive feel to it. The old carapace of dull Soviet influence is giving way to a more dynamic town that is courting international interest and foreign investment.

There’s a beautiful reminder of Russian influence in downtown Panfilov Park: the Russian Orthodox ‘Ascension Cathedral’ which was built without nails and which survived a severe earthquake in 1911. Russians – those who did not return to their homeland after the collapse of the USSR – worship here.

Although dominated by native Kazakh people, Almaty retains a Russian European flavour. Perhaps this city has always looked north to Russia rather than east to oriental China or west to Moslem Central Asia.

Uzbekistan

_________________________________________________________________________

TASHKENT

Tashkent. Two men in Uzbek costume on the railway platform welcoming arriving passengers with blasts from two metre long trumpets. Another two accompanying the noise with a flute and drums.

What a contrast.

No Orthodox cathedrals here. Moslem architecture and clothing. Grand structures in blue ceramic tiles, and equally impressive Uzbek ladies in multi-coloured silken garments. Perhaps a head-scarf, perhaps not, for the Central Asian communities practice a moderate form of Islam. Our Moslem tour-guide says he is married to a Christian. Later on in Turkmenistan, a blond-haired Caucasian guide from Armenia will inform us that he is married to a Moslem. All good.

Fundamentalists have tried to stir up trouble here, but have not found the support they hoped for. Official Russian atheism and private orthodox Christianity probably ensured that Moslem extremism did not get a foothold and the locals seem happy about that.

I chat with an Uzbek teacher and her class who are visiting a mosque. A mix of Uzbek, Tajik, and Russian kids, wanting to say hello. Then I have my photo taken with a group of middle-aged ladies in traditional colourful clothing. Friendly and happy to meet a foreigner. Locals looking outward to the West rather than inward to Moscow.

A small Russian Opera House on the edge of a park. Deserted by many of its patrons who have returned to mother Russia. The park containing a memorial to Uzbek lives lost in the defence of Russian territory in World War II. Too many of them – Central Asian troops played a big role in the defence of Stalingrad. Next door, a modest but reverent Tomb for the Unknown Soldier. Unlike its copy in Almaty, there is no Soviet triumphalism here. Just plain, unadorned grief.

Tashkent. Russian influence giving way to a resurgent local culture.

SAMARKAND

Crossing the Syrdarya River which originates in the Tian Shan Mountains in Kyrgyzstan and eastern Uzbekistan, and which flows for 2,200 kilometres west and north-west through Uzbekistan and southern Kazakhstan to the Aral Sea. A dead sea of abandoned rusting vessels beached on the bottom of a bone dry lake.

The Syrdarya and its twin, the Amudarya further west, have been bled dry by a thoughtless or deliberately short sighted agricultural policy of irrigating thirsty cotton crops with a finite resource. You can thank Soviet bureaucrats for that idea.

Then the first taste of a Central Asian desert. Small barren villages stealing a little space from the sandy expanse. Clinging to the railway line for dear life. Worn, weather-beaten trees looking like they need a drink. Just like the people.

Then Samarkand. Fabled exotic object of many a poet’s dreams. Explorer’s also. Arguably the cultural heart of the Silk Road. A destination rather than a stop-over.

Registan Square demanding attention. Imposing. Magnificent and proud. Moslem proud. Large scale Madrassars promoting Islamic arts and architecture. Blue-tiled arches, minarets, and domes. Inside, alcoves and ceilings delicately crafted in subtle shades of blue, green and white.

Awe inspiring.

Yet, it’s a soulless place, and I’m not sure why. Maybe these people are still recovering from Russian dominance. Maybe the so-called moderate Moslems here lack true piety? Maybe their government leaders are communist chameleons who, fearing the potential for Moslem resurgence, control everything with a strong hand behind a façade of democracy ?

Who knows?

Nevertheless, the Madrassars are magnificent and it is possible that I have expected too much from such a short visit. You need time to get inside a culture.

Next stop, Bukhara.

BUKHARA

The train rocking and rolling across more desert. Dusty tracks running beside the rails, sometimes branching off into the distance, heading toward the horizon and whatever lies beyond. Passing depressed railroad villages with their tired dwellings and slow-moving locals serving life sentences of railway maintenance boredom.

The ancient walls of this Khanate were formidable obstacles for any potential conqueror. Because the old walls have been degraded by time, the United Nations has funded their reconstruction – a sacrilege to the purists, but a thing of beauty and history for ordinary travellers anxious to discover what life was like here all those years ago.

Bukhara has a history. An object of The Great Game played between Russia and England in the 19th century, and home to a series of cruel and treacherous Emirs who, because they had no knowledge of the outside world, believed that they were the equal of the Russian Czar and the English Queen.

These petty tyrants had also enslaved thousands of Russians among others. Eventually, and after a couple of failed attempts, a Russian army sent them packing when they moved south to include this part of Central Asia in their empire.

For the local people, this occupation materially improved their lives. For the British, it was a worry for they feared Russian expansion. Central Asia today, perhaps their Indian colony tomorrow?

Turkmenistan

_________________________________________________________________________

The Amudarya River roughly traces the border between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. It drains most of Tajikistan, the southwest corner of Kyrgyzstan, the northeast corner of Afghanistan, plus about half of Uzbekistan. But it enters the barren Aral Sea with nothing to show for itself. No water, just a few lines on a map. What an environmental catastrophe!

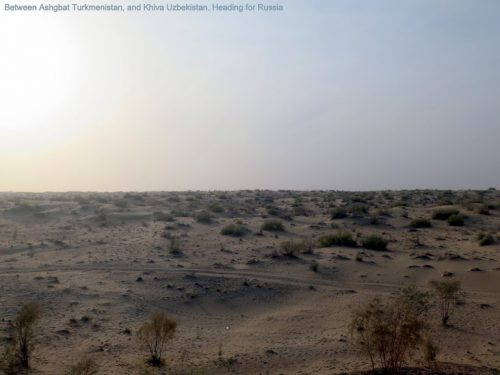

This river is the last decent waterway before the Karakum desert: an arid, forbidding expanse bordered in the south by the dry Iranian and Afghanistan Plateaus, and in the west by the Caspian Sea. It’s a lonely, desolate place, and it’s a long way between oases. Hot in summer, and freezing in winter.

Think of the caravans of yesteryear.

And think of the roaming, nomadic bands of tribal Turkmen who robbed and murdered, or sold their victims into slavery.

And these were just the locals. Genghis Khan and Tamerlane were much worse. These terrorists slaughtered everybody and destroyed everything just for the hell of it.

MERV

Merv is located in the southern Karakum Desert and in Persian legend, was the birthplace of mankind. When you think about it, quite a claim to fame for such a small hot and dry oasis in the middle of nowhere.

This city was an important post on the trade routes to the east from before the 3rd century BC. After its capture by Muslims in 651 AD, it became a major centre of Islamic learning.

From ground-level, it is unimpressive. Remnants of ancient long walls heading off in apparent different directions demarcating large swathes of territory. When you look at a topographical map however, everything makes sense. Unlike other ancient ruins where new cities were built on old ruins, succeeding cities were built adjacent to one another. Hence the large area covered.

For example; Merv contains the ruins of five walled cities from different eras: Greek (3rd Century BC), Sassanian and Western Turk (4th – 7th centuries), Arab (8th century), Seljuk (12th century), and a city which was built after Genghis Khan’s rampage in the 13th century. All of them contiguous to each other.

UNESCO is in charge of restoring these ancient sites. A big job.

The Karakorum desert covers most of Turkmenistan, and is a dry, sandy wasteland with only history to recommend it. One wonders if the harshness of this environment shaped the sometimes cruel behaviour of its leaders and nomadic outlaws.

ASHGABAT

Founded by the Russians in 1881, and independent since 1991, Ashgabat is the capital of Turkmenistan, and is known as the Las Vegas of the Karakum. Forty kilometres from the Iranian border, this recently constructed city is a monument to the ego of the first president and dictator of modern Turkmenistan, Sapamurat Niyazov – the old Communist party chief. Oil and gas wealth funded this tasteless extravagance.

Futuristic building designs (all in white) shout; ‘Visit Ashgabat and marvel’; and ‘Notice Ashgabat – notice me’.

It’s a bit hard to avoid this man anyway because his portrait is on every building and his statues are everywhere. He has even re-written the Koran to include himself (where are the fundamentalists when you need them?)

Yet, when I visited this garish place, save for a few cleaners and a handful of people wandering around looking like they shouldn’t be there, this futuristic part of the city was dead. No hum of activity, no commerce, no noise, and little traffic. President whatsisname’s mausoleum to himself (his successor is a clone, so we won’t bother describing him).

Yes, interesting buildings if you like grandiosity and architectural exaggeration for its own sake. For example; the library is shaped like an open book. That’s not so bad, you might think; but when you see a dental school shaped like teeth, you see a pattern and begin wonder…

Self-engineered heroic cult status writ large. The most pompous architectural departure from reality I’ve ever seen.

The tour guide in our bus seemed happy though. Praising his president for subsidising health and housing (no grandiose buildings, just functional apartment blocks lined up in regimental rows outside the Ashgabat inner sanctum – Niyazov’s Disneyland), and assuring us that everyone who lives in Ashgabat is content with their lives.

He would say that, wouldn’t he.

And who am I to argue?

Some people on my tour thought the place was wonderful.

The saddest thing about modern Ashgabat is the lack of any evident cultural or environmental link to the past. Yes I know this place is famous for its carpets and fabrics, and I know that the old city was destroyed by an earthquake in 1948, but that was a long time ago and that’s no excuse. Vibrant cultures usually survive environmental catastrophes.

KHIVA

Back to the Karakorum Desert and the long journey to Khiva on the Amudarya River, 500 kilometres north of Bukhara. Nothing to see from one horizon to the other.

Although Khiva is of little importance today (current population 40,000) its history dates back to the 6th century. It was a small town on the ancient part of the Silk Road which stretched to the Caspian Sea and the Volga River in Russia – our next destination.

In the 1800’s it had a well-deserved reputation for barbaric rulers, and was famous for its slave market which was fed by marauding Turkmen bandits. The town was reputed to have 30,000 slaves including a few thousand Russians who provided good enough reason for a Russian army to conquer it.

Unfortunately, the first attempt failed. Beaten by poor planning and logistics and the worst winter snow in decades. However, in 1873, General Kaufman completed the task and brought the Khanate of Khiva into the Russian orbit.

From Khiva, Russia extended its influence to the southern parts of Central Asia, and maintained this hegemony until the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Today it is included in the independent state of Uzbekistan.

These days, Khiva is a good place to soak up history as you photograph the Moslem architecture and buy colourful local fabrics.

Next stop Volgograd (Stalingrad) on the Volga River in southern Russia.

But first, more desert. It’s everywhere. The Nothing. Threatening to swallow anything that gets in its way.

Russia

_________________________________________________________________________

VOLGOGRAD (Stalingrad)

Crossing the Russian border. At first, more of the same. Desert.

Then semi-desert. And then crossing the famous Volga River. Now suburbs. Nothing special, just ordinary dwellings.

Then Volgograd railway station and a musical welcome from local Cossacks in mufti. A big improvement on the trumpet blasts of Tashkent railway station. It’s another world here. No desert and no Moslem madrassars.

Europeans. Russsians and their Russian history and culture. In Volgograd it’s in your face, and the old Party propaganda machine is not about to let us forget Soviet Russia’s resistance against the Germans in World War II.

But I have done my homework. I have read the books and learned that German soldiers had to get out of their tanks and engage in hand-to-hand fighting with Stalingrad’s desperately heroic defenders – many of whom came from Russia’s Central Asian provinces. For example, the famous sniper immortalised by Hollywood was not a handsome Caucasian, but a Kazakh man with Mongol features. An illiterate conscript from the Steppes of Asia.

Despite my admiration for the defenders, and my sorrow for the fallen, I find the political nature of Soviet triumphalism a little distasteful. This unlikely victory which turned the course of the War belongs to the humble infantrymen who fought it, and not to the Soviet state.

And on that note I conclude this narrative on the Silk Road with an observation that the desert countries of Central Asia appear to be better off now than they have been for a long, long time. With good leadership, they will prosper.

Although I will continue my journey on to Moscow, that beautiful city and its art and culture and history are another story. Fascinating, but apart from its own difficulties with the Mongol hordes, one that is not relevant to this tale.