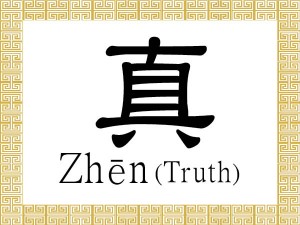

In China: what is truth?

Brian Hennessy. An Australian in China. April, 2015

It’s always difficult to comment on China. Paradoxically, this rigid Confucian society appears to change from one day to the next. Whether this is cultural reality or personal confusion, I am not sure. Nevertheless those of us who have lived in the Middle Kingdom for a long time have learned that things are often never as they appear.

In China: what is truth?

____________________________________________________________

China is a materialistic society. It is rare to meet folk who have a deeply held personal belief system which generalises across day to day situations. Personal ethics may vary according to the situation.

For example; although one might behave ethically and morally within close personal relationships, one’s behaviour outside such intimate circles – if I can put it delicately – may be more adaptive. That’s why the first rule for survival in China – for natives as well as expats – is to protect oneself first.

So, let’s be clear about one thing: although Confucianism is the bedrock of Chinese society, it is important to recognise that generally speaking, it is more a collection of culturally appropriate rules and behaviours rather than a personal guide for individual morality.

A qualification: not all Chinese people behave this way. Some of my acquaintances are the most moral people I know. A contradiction that might be better understood via Taoist rather than Confucian wisdom (a topic for another day, perhaps).

Nevertheless, one might assume that after having lived for so long in the Middle Kingdom, I should be less troubled by these cultural inconsistencies than I am. Further, one might also assume that by now I would have an informed opinion on where China is today and where it is going tomorrow.

This is dangerous territory – there’s a fine line between informed opinion and loose speculation where China is concerned. As some Western observers demonstrate, it can be easy to surmise and predict if one looks at China from a distance. The ruffles of cultural and political complexity appear smoother from afar.

It is not so easy to form an opinion however, if one is immersed in the realities of life in mainland China. The Middle Kingdom is a much more complex society from this perspective.

In fact, the years spent in China have forced me to confront an inconvenient truth: no matter how well we Western expatriates might think we understand China, the reality is that we will always be foreigners in this mysterious land. We will never know as much as we hope to know about this ancient society and its modern rulers.

There is always much more going on than meets the eye, and it can be difficult (for Westerners) to read between the lines and discern fact from fiction. Political pronouncements should always be taken with a grain of salt.

For example, past president Deng Xiaoping’s cautionary advice to his countrymen to be humble and cross the river by feeling the stones beneath one’s feet was a wise aphorism three decades ago.

These days, China knows exactly where it is going and how it will get there.

It keeps us guessing though. So we Western observers monitor China’s progress from the riverbank and speculate: forever running the risk that today’s old-China-hand opinion could well be tomorrow’s reputation-deflating embarrassment.

Most professional China watchers seem untroubled by such self-doubt however. So their media outlets accept their speculations readily. They (particularly those based in offshore Hong Kong) believe that because they have a government source in mainland China (every commentator worth his salt has one), they are privy to inside information.

Suckers. This is how the Communist Party of China disseminates misinformation.

There are no truths in China. Truth is relative. Truth is what the government says it is, and truth is what your mainland Chinese sources may manipulate if it serves their purpose. Truth may change from day to day.

The Western ideology of Communism does that to societies. It degrades natural goodness. It forces people to discard traditional values and replace them with opportunistic or self-protective behaviours.

Eventually this corrupts both culture and country.

In China, ancient cultural hierarchies and their respectful sensitivities are being harmed by blunt instrument power politics. An ugly underworld lies beneath the beauty of traditional Chinese culture.

Perhaps living in a bi-cultural no-mans-land has finally got to me. Maybe it is time to return permanently to my home culture and write my memoirs.

No. Not yet.

This is the beginning of wisdom.